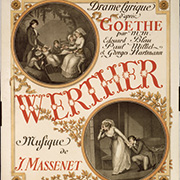

Massenet’s operatic masterpiece Werther has a complicated history of composition. The new Bärenreiter edition presents an authoritative version created on the basis of all the available sources.

Massenet, the leading composer of French opera in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, was a consummate craftsman and man of the theatre. At the head of his long list of works are two born in the 1880s, Manon and Werther. Both are based on eighteenth-century literary classics, but are otherwise quite dissimilar from one another. Many would rank Werther as Massenet's masterpiece, even though it has not been performed as often as Manon in the 125 years since its world premiere, nor was it as quickly embraced by the public in its own time, despite attractive music of great emotional intensity and an excellent libretto. A generally tepid response by early audiences was due partially to a distaste for the introspective and dark subject, but difficulties in casting the leads may well have delayed appreciation of the opera as well. Despite a warm welcome at its Viennese premiere, the work went on to only 56 performances at the Opéra-Comique in Paris between 1893 and 1902; and, in 1894 it failed miserably in London. Massenet's epic struggle to locate just the right tenor to play his troubled romantic hero at the Opéra-Comique not only delayed the Parisian premiere from November 1892 until 16 January 1893 (giving Geneva the honour of the first production in French on 27 December 1892) but may have spurred him to prepare a baritone version. With this, it was reported that he hoped the great actor-singer Victor Maurel (who was Verdi's first Iago and Falstaff) would sing the role at the Opéra-Comique in April 1894 and then take Werther around the world with him.

Basically a loosely knit number opera, and planned as such in an early scenario, Werther features closed vocal forms (Charlotte and Werther sing four duets, one in each act, and Werther has four solo numbers). It also makes notable use of recurring motives, various techniques to ensure continuity, and parlante texture. "La Nuit de Noël," an effective orchestral tableau, opens Act 4 and links Massenet's highly successful third act to Werther's death scene. This poignant score of great intimacy features only one or two characters in its most striking moments. For these passages, the principals must sing well, act convincingly, and deliver Massenet's meticulously shaped lines with sincerity and finesse. There is no ballet or chorus, except for the six children of the Bailli.

Though he wrote much of Werther in the mid-1880s, Massenet had been thinking about the subject for years prior to that, and he held the work close to his heart. As early as 1880, when a basic outline was probably available to him, he told a friend that Werther was a "very unusual work [...] designed to satisfy me first of all." Many years later Guillaume Ibos, too, stressed that Massenet set great store by this opera and its success, because "it was his own life as a man and musician." Although Ibos had a tendency to embroider the truth late in his life, particularly regarding his contribution to Werther's history by taking on the title role at the last minute to make the Parisian premiere possible, this assertion seems to hold some validity. In fact, the opera's significance to Massenet personally, its long genesis, and its slow acceptance by the public help explain why for more than a decade the composer repeatedly polished and tinkered with a score that was already admirably crafted.

To best represent Massenet's definitive intentions, this critical edition evaluates and takes into account changes that appeared in the multiple orchestral and piano-vocal scores published during the composer's lifetime. It is the first edition to do so. The 1887 autograph manuscript (used by the engraver to prepare the first orchestral score) must serve, of course, as a basic resource, even though it does not necessarily reflect Massenet's final thoughts on all the elements he decided to alter both before and after Werther's world premiere at the Vienna Hofoper (16 February 1892). The several versions of the orchestral score issued by Massenet's publisher Heugel before 1912 differ from the manuscript, from one another and from the piano-vocal scores of that period.

Interestingly, the autograph manuscript complicates the process of establishing an authoritative text because a copyist wrote out most of the vocal parts; thus, other sources from Massenet's lifetime take on an increased importance, as, for example, his copy of the piano-vocal score, which documents his ideas on staging and changes to the music, or numerous other printings of the piano-vocal score, where alterations to the vocal line and/or text, expression markings, dynamics, and staging gradually appear, until finally a stable form emerges. In a notational style so minutely controlled—and it should be stressed that Werther pre-dates Debussy's groundbreaking works by only a few years—determining which details were decided upon is essential, especially with respect to Massenet's precise communication with his singers. As one who attended numerous rehearsals and often coached his principals, Massenet engaged in a reciprocal process, learning from his performers as well as instructing them. This critical edition of Werther traces, explains, and reconciles differences among the sources from Massenet's lifetime (something the composer himself never managed to do), acknowledges the libretto's role, corrects errors and omissions, and suggests alternative pitches for the timpani (presuming that modern timpanists have access to three, easily tuned instruments rather than two). Critical notes make earlier readings accessible and explain how Massenet wished staging and music to work together.

Appendices include the original pp ending of the "Lied d'Ossian" and (from the archives of the descendants of the Van Dyck family) a transposition of this Lied that Massenet prepared for Ernest Van Dyck, the first tenor to sing the title role. The supplementary materials also offer the earlier version of Charlotte and Werther's Act 4 duet, which Massenet revised before the first piano-vocal score was published in order to reduce the amount of singing required of the mortally wounded Werther and give the lovers a chance to embrace. Also contained in the appendices is a detailed staging manual in its various stages. This source was closely coordinated with the piano-vocal score and is of particular interest because it likely stems from a collaboration between the Opéra-Comique director Léon Carvalho (unnamed in the manual) and Massenet during the extended rehearsals of autumn 1892 prior to the Parisian premiere on 16 January 1893.

Lesley Wright

(translation: Elizabeth Robinson)

(from [t]akte 2/2016)