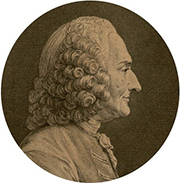

Jean-Philippe Rameau died 250 years ago in September. His operas and ballet music are increasingly finding their way back into the theatrical repertoire. Three works have just been newly published in the Complete Edition.

Spectacle and supernatural scenes. “Dardanus” 1739

According to all evidence the first version of Dardanus was composed in just six months. It was first performed at the end of 1739 and constitutes a notable work in what was an extremely productive phrase for Rameau during which he composed five major works. These works – the three tragédies (Hippolyte et Aricie, 1733; Castor et Pollux, 1737; Dardanus, 1739) and two ballets héroïques (Les Indes galantes, 1735; Les Fêtes d’Hébé, 1739) – were performed within a six-year period at the Académie royale de musique in Paris. Other works also written during this period include Samson (1734, written in collaboration with Voltaire and banned by the censor), the music to the pastoral Les Courses de Tempé by Alexis Piron (1734) and the publication of Génération harmonique (1737).

This first version of Dardanus had a run of 26 performances (Castor et Pollux 21 performances, and Les Fêtes d’Hébé 71 performances). The notable cast with Jélyotte (Dardanus), Mlle Pélissier (Iphise), M. Le Page (Teucer and Isménor) and the dancers Dupré, Salé and Barberine certainly made its contribution to the work, as did the revisions which were quickly and effectively undertaken by Rameau and Voltaire from December 1739. The inspired verses maintained a high level of interest in the opera, as did the plot drawn from Greek mythology which deals with the characters involved in the founding of Troy and the origins of the Trojan dynasty: in the war between the future founders of the city, Teucer fights with his Phrygian people against Dardanus and his troops. The latter loves Iphise, the daughter of his enemy, and she reciprocates his love. The key elements in the libretto are the monologues of Iphise (1st and 3rd acts), who is pulled in conflicting directions between her love for Dardanus and her faithfulness to her father and people, and in particular the spectacle and the supernatural visions, the “merveilleux”.

The pretext that Dardanus, as a son of Zeus, was of divine birth, was, incidentally, demanded by the librettist and does not come from the classical model.

Such an effect-laden text also had the advantage that it held an exceptionally stimulating fascination for the composer. Rameau knew how to raise the level of his music to match this large-scale spectacle and supernatural scenes. Examples of this include: the prologue, in which Venus and the personification of envy and their retinues collide; Anténor’s pledging of allegiance to Teucer, who promises him the hand of his daughter in return (1st Act); the magician Isménor’s spells (2nd Act); the dreams of Dardanus and the fight of Dardanus and Anténor against the dragon (4th Act), whose appearance is prepared from the end of the 3rd Act, and the finale duet by Vénus and Dardanus, in which the power of love is celebrated (5th Act).

Cécile Davy-Rigaux

Voltarian dialectic with bird sing. “Le Temple de la Gloire”

There are two versions of Le Temple de la Gloire, Rameau’s sole surviving opera to a libretto by Voltaire. The first performance of the first version took place on 27 November 1745 in Versailles on the occasion of the celebratory reception of Louis XV, who had won a victory in Fontenoy a few months earlier. Voltaire was far from having to flatter the King, as the court poet was obliged to do, or as Quinault did in the service of Louis XIV. He produced a philosophical opera, followed by a series of (unsuccessful) libretti: Tanis et Zélie, Samson and Pandore/Prométhée. With reference to Metastasio, he attempted to moralize the opera, to free it from the galant milieu in order to lend it seriousness and to transform it into a large-scale, edifying and political stage work. Le Temple de la Gloire is presented as a dialectic ballet: after a prologue devoted to the personification of envy – a reference to the prologue from Quinault’s first opera which Voltaire wanted to equal – the over-resolute tyrant Bélus and the over-indulgent tyrant Bacchus are ejected from the Temple of Glory; in a sublime scene inspired by La clemenza di Tito or Cinna, ou la clémence d’Auguste, Trajan is crowned with a laurel wreath because it was he who defeated the rebels, particularly because he forgave them and then transformed the Temple of Glory into a public Temple of Universal Happiness.

In December 1745 the work was revived in the Paris Opéra, but was a failure. As a result commemorizing both composer and author withdrew it in order to rework it. The premiere of the second version took place on 19 April 1746 at the Paris Opéra and was also a failure.

However, there are many notable passages in the music: for example, the unusual ‘themeless’ fanfare for two small recorders, two trumpets, two horns, timpani and traditional orchestra of strings and reed instruments in the overture; the famous monologue “Profonds abîmes du Ténare” with obbligato bassoons; and Trajan’s refined finale scene “Ramage d’oiseaux”.

Voltaire’s libretto was published in its 1745 version during the author’s lifetime, whereas the first publication of Rameau’s music only took place in 1909 as part of the Complete Edition directed by Saint-Saëns, this being the 1746 version. Therefore, for a long time, it was assumed that the 1745 version was missing. But a relevant manuscript came to light: once owned by Alfred Cortot, this is now preserved in the University of California, Berkeley, USA. It contains several hundred bars (corresponding to more than two acts) of previously completely unknown music by Rameau. With Volume IV.12 of the Opera omnia Rameau, a complete edition of the Temple de la Gloire is published for the first time. This comprises a double edition of the libretto, full score and vocal score, containing additions and cross-references, thereby enabling the performance of both versions.

Julien Dubruque

The Nile owerflows. “Fêtes de l’Hymen et de l’Amour”

This ballet-héroïque in a prologue and three entrées (Osiris, Canope, Aruéris) was first performed on 15 March 1747 in Versailles on the occasion of the wedding of the French dauphin and his second wife Maria Josepha of Saxony. Initially, the work, based on a libretto by Cahusac, was intended for the Académie royale de musique under the title Dieux d’Égypte. Subsequently the ballet was performed in Paris and repeated in the various court theatres with great success (1748, 1753, 1754, 1762, 1765, 1772, 1776), ultimately achieving a total of 150 performances. For a long time the work was regarded as being of secondary importance because its premiere was linked with a political event, but it is full of dramatic innovations which give an idea of Rameau’s later operas, such as Zaïs, Zoroastre and Les Boréades.

In this ballet, Rameau and his librettist Cahusac attempted to integrate dance numbers, choruses and stage effects more closely into the main plot. He also experimented with musical styles, something which remained unique within his work. The most famous of these is undoubtedly the scene in which the Nile overflows – an impressive ten-part double chorus with soloists and orchestra, and the sextet from Aruéris, an incomparable setting for Rameau. A novel feature was also the combining of musical forms, and the refined, aria-like recitative in the Egyptian ballet in the Aruéris act; here, the orchestral writing displays innovative approaches in some of the dances.

Even though it received numerous performances, Fêtes de l’Hymen et de l’Amour was barely revised by Rameau. As most of the performance material from the premiere was lost, this new edition is based on the version created in 1748 for the Académie royale de musique. This barely differs from the first version, apart from the fact that two ariettas and a number of dances have been newly included. With ensembles with modest resources in mind, this edition offers practical performing arrangements reflecting the revisions of the work made in 1753 for the performance at the Théâtre royal in Fontainebleau, and then retained for the performances in 1762, 1765 and 1776. These enable the Aruéris act to be performed by forces requiring three fewer soloists, that is, with a total of just four soloists.

With this critical edition of the Fêtes de l’Hymen et de l’Amour, a benchmark version of the work is published for the first time, based on all the important sources for the libretto and the music (in particular taking two new discoveries into account).

Thomas Soury

(from [t]akte 2/2014)