The confrontation of religions was as current at the time of the Old Testament as it is today. One such conflict takes centre stage in Handel’s oratorio Samson until its fatal outcome.

Samson was one of Handel’s most frequently-performed works in the 18th century. In the second half of the 20th century the number of performances decreased compared with Handel’s other works. Is this because of changes in our ethics, which are now based more on global than national matters? Is it because we can no longer unconditionally align ourselves with one side in the battle of religions? What chances does an oratorio such as Samson have in the 21st century, which teaches us through a violent shock right at the beginning to abhor every suicide attacker? Yet this is not concerned with condemnation or justification. A closer look at Handel’s Samson shows that such reflections do not go far enough.

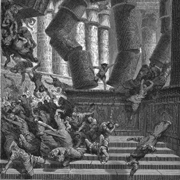

The story of Samson, of his mysterious physical power, the Philistine girl Dalila, who elicits his secret from him and betrays him to his enemies, and his last heroic act, the destruction of the Philistine temple, is well-known from the Old Testament. The direct model for the oratorio was a piece of world literature, John Milton’s verse drama Samson Agonistes. It concentrates Samson’s story into three encounters with the shackled hero on the last day of his life, and presents it as a tragedy.

We become witnesses to his deepest despair: the high-handed strongman, who had taught the Philistines fear by his high-spirited pranks and bloody slaughter, now lies on the ground, beaten, shackled, blind, oppressed by slave labour and without hope. Worse than the ridicule of his enemies, he is now affected by the sympathy of his friends, particularly that of his father, who mercilessly depicts the contrast between the past and the present for him. Samson no longer sees any point in his life and longs for a speedy death. Dalila, here cast as his wife, offers to strive for his release and to care for and cosset him for the rest of his life. Samson resists the temptress. Finally he is confronted by his former self in the form of the Philistine Harapha, a giant bristling with muscles. Samson exposes him as a braggart.

In these three dialogues, right is by no means clearly on Samson’s side. His adversaries have good arguments; the clashes are thrilling. Dalila is portrayed as intelligent and attractive, particularly in music. At the end, Samson sees the possibility of giving his life some purpose once more as a fighter for the freedom of his people, which is possible, but only at the cost of his life.

Of course, Samson’s act of liberation is celebrated. But this conclusion was not the one originally planned by Handel and his librettist Newburgh Hamilton. The oratorio was intended to end peacefully with a requiem for Samson. Milton recalls in his foreword that from time immemorial, tragedy had the power “by raising pity and fear, or terror, to purge the mind of those and such-like passions”. Handel’s music still has this power even today. His oratorio aims to shock the listener, rather than encouraging him or her to take sides. The help Handel offers us in coming to terms with the horror could be sought-after again today.

The original version, ending in mourning, has never been performed. The jubilant finale which Handel added in 1742 – probably bearing his audience in mind – does not celebrate Samson’s deeds, but God’s Providence. At Handel’s request, Hamilton reworked the celestial consort from Milton’s poem "At a solemn music” for this. In addition, as part of this reworking, the Philistines were given a more prominent part. They are characterized musically as a happy, celebrating, and by no means uncongenial people. Through Handel’s arrangement, the oratorio gained more colour and variety, without abandoning its tragic character. For those who want to emphasize these qualities, the Halle Handel Edition offers the possibility of performing the original version for the first time. It can be reconstructed, apart from a half aria.

In addition, this edition makes available all known versions of the oratorio which Handel himself performed. As hardly any performances of this long work take place without cuts, the publication of all the authentic cuts in a reliable edition should be welcome. The parallel presentation of cut and full recitatives adds to the practical value of the full score and vocal score.

Hans Dieter Clausen

(translation: Elizabeth Robinson)

(from [t]akte 1/2012)