A concerto? The form of the solo concerto has long been regarded as obsolete, and composers have avoided writing in this tradition. But Philipp Maintz isn’t one of them. He described in an interview why he writes concertos.

Concerto form has at times been regarded as a “non-form” – particularly in the postwar New Music scene here in Germany, as it was misjudged as a relic of bygone, vanquished historical epochs. Above all, the performing soloist, or even his or her position on stage as an orchestrally-accompanied virtuoso, was regarded as highly suspicious. Despite this, in that period there were also concertante works, close to concertos, often called “Music for ...”. However, for some considerable time there has been a counter-movement once again in favour of the concerto, as reflected in the programmes of various festivals.

[t]akte: In your opinion, what has brought about these changes? What motivates you to write concertos?

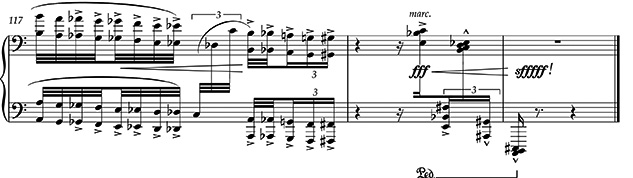

Philipp Maintz: I remember commentaries in programme booklets (I was 15 or 16 years old), where there was discussion about the fact that pieces would evoke a “traditional” concert situation – and then there was the typical phraseology that when the piece began, “everything would indeed be different”. I never understood that. I remember lessons with Michael Reudenbach (I was then 17 and once again wanted to write a piano concerto), and he grumbled that people shouldn’t write piano concertos nowadays, that it was no longer socially responsible for an 80-strong orchestra to “musically wash the floor” for a soloist … For me that’s understandable from a certain historical point of view (although the 1950s, 60s and even 70s are long gone, but remain in the memory, at least aesthetically in Germany to the present day as reference points). But for me, particularly with the piano, the virtuosity of a soloist, the feel, and with some pianists the physical beauty and elegance of their playing inspired me. Somehow I’m always happy when a grand piano is rolled onto the concert platform and the lid is raised promising much. I then prefer not to be served up with a piano concerto where everything is “quite different” and, out of pure political correctness, the soloist hardly plays. In the last few years I’ve met a number of truly outstanding pianists who have all given me a tremendous desire to write piano music. So, a concerto with pianistic stunts, taking pleasure in the solo instrument in front of the orchestra – and a proper piano concerto ending!

With your concerto for piano and large orchestra this isn’t the first time you’ve engaged with the concerto genre, as you’ve revealed. What “predecessors” are lying in your cupboard?

Piano concertos form the foundation of my musical socialising: because of recordings in my father’s LP collection I could whistle along to the Beethoven and Mozart concertos from my earliest childhood. Later on I liberated myself from the LP collection. The Prokofiev concertos made a deep impression on me, the first two by Bartók in particular, Schoenberg’s concerto baffles me to this day, but I like it, likewise the one by Ligeti. And of the more recent piano concertos, my number one is Lutosławski’s! Since then I have tried, of course, to write piano concertos. The first was in 1989 (something of an epic piece and a stylistic muddle), then a second in 1990 (with an opulent scoring) and then in 1991 a third (never quite finished). Then later, as a pupil of Reudenbach (around 1994 or 1995), I tried to write another piano concerto, but that sank in the discussion I just mentioned. So what remained? This sense of anticipation when a grand piano is wheeled out in front of the orchestra and the desire to write a piano concerto ...

The “Sinfonia concertante” form also seems to have life left in it, as your new work sur tourbillon. music for bass clarinet, violin, violoncello, piano and ensemble emphatically demonstrates. But why do we encounter the rather neutral title “music for …“ here?

This “music for ...” title is a mannerism which I’ve carried around with me since the 1990s, and which I want to drop with the piano concerto. I didn’t intend sur tourbillon as a “Sinfonia concertante”, but rather as a corona around the soloists, emerging from the development of the piece. It was written as the next generation of the piano trio tourbillon (2008). The concertante idea has no initial significance, but is nevertheless close to it: the nucleus of this piece is the piano trio (expanded by the addition of a bass clarinet), it radiates into the ensemble. There is a certain interaction between soloists and ensemble implied, which of course sounds “concertante”.

The “concerto” has been one of the great “public genres” since time immemorial – in contrast to chamber music. Do you offer the soloist a forum for displaying his or her virtuosity?

With the piano concerto it was important to me that it is a “true” concerto. And I think that I only found a way of writing for piano which I regard as sufficiently “grown up” for a concerto with my baritone song cycle windinnres (2011/13). The piano concerto has, in comparison with my klavierstück no. 2 (piano piece no. 2) (2006), a much more elegant and distinguished style which intensifies in the last movement into the ecstatic. The orchestra quite clearly follows the soloist, weaves threads leading further, and is to the soloist a reverberating space, echo, stage, dance partner and tightrope for balancing acts. For me, instrumental virtuosity is not only combined with technical brilliance, but it fascinates me just as much when a pianist, in self-absorbed contemplative intimacy, allows the piano to sing in velvety tones. And so I arrived at these points where the orchestra steps back or is silent and the pianist either creates spun loops and spins yarns to him or herself – or else storms away from the tempo until he or she is caught again by the orchestra, and they continue on the journey together.

Can you outline how the first impression of the concertante dramaturgy, the formal idea, is adopted or modified during the process of making a fair copy of the score?

In the piano concerto it is the confrontation with the traditional concert form programme: the piece indeed has four movements which I have pushed into each other using a fractal model and from the perspective of dramaturgical urgency. But it’s always the piano which formulates the central ideas. From the kaleidoscope-like arrangement of the movements came the possibility of re-using ideas and gestures – to a “re-thinking” between orchestra and piano. And there is the situation (greatly valued by me in formal terms), when the orchestra follows the soloist in a sort of slipstream turbulence; it’s in the fourth movement that the two drive each other on further, whipped along.

Now you’re now writing another concerto, a cello concerto. After the four-movement piano concerto might you now pursue other formal and dramaturgical plans?

As an instrument the cello has a completely different character from the piano. This strongly determines the sound I have in mind. It’s always so: whilst I am writing a piece, my imagination wanders off in another direction and suggests caprices which don’t exactly suit the situation. The potential of the form of the piano concerto is to my mind nowhere near fully exhausted. I’d like to drive it in another direction once more. And for a long time, new images have been forming in the back of my mind: it would be lovely to have written five “piano concertos” one day – and one of them a real hit like Prokofiev’s third ...

Interview by Michael Töpel

(from [t]akte 2/2014)