The source material for Bach’s Mass in B minor is complicated. In order to create a practical performance version, compromises had to be made. Uwe Wolf describes how he approached his edition.

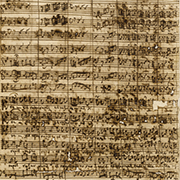

Bach’s manuscript was “X-rayed”. The use of a modern scientific process helped us to get much closer to the secret of Bach’s Mass in B minor. How come? The iron gall ink erosion in the autograph manuscript of Bach’s Latin mass – particularly in the “Credo” – is legendary. The holes now present in the autograph manuscript are, however, more of a symptom. The real problem is the many corrections which not only considerably reduce the legibility of the score, but have also advanced the iron gall ink erosion. There are corrections in various different hands: as well as Johann Sebastian, these are by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach in particular. Therefore our interest lies not only in the last variant reading, but also in the question of who made corrections, and what was there before the son intervened. In this process, various copies of the Credo made between the deaths of Johann Sebastian and Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach help us. Many of the interventions can be undone with the help of earlier copies – not with absolutely certainty (after all these are just copies, not photographs!), but with a high degree of probability. However, this doesn’t work at all with the first layer of revisions: Bach’s son went through his father’s autograph manuscript thoroughly before he gave it to the first copyist to make a copy; the text added to the copy alone (which precisely follows the son’s revision, including all gaps and oversights) substantiates this more than adequately. This first stage of this work by Emanuel was probably also urgently needed, as some corrections by his father had not been carried out in full. Here, the son had to complete this work.

All corrections which we were unable to attribute by using the copies to one of the later rounds of corrections by the son, and whose author is no longer clearly identifiable, are suspected of having been made by the son, as are all those places which later fell victim to the iron gall ink erosion.

At the outset of making this edition, therefore, many of the problematic corrections in the autograph manuscript were examined by using x-ray spectography, a non-destructive method of ink analysis. In this way, it was possible to attribute a number of passages to either father or son – with some surprising results (which could then also be visually confirmed in the autograph manuscript).

But plenty of unresolved cases remain! In the new edition published in the New Bach Edition. Revised Edition (Bärenreiter 2010) everything in the “Credo” which is not definitely by the father is therefore set in square brackets – whether it was because it was eroded, or because the father’s writing is no longer legible, or whether it was a variant reading by the “old Bach” which no longer made sense and had justifiably been corrected by the son. In these cases particularly there is always some scope for discretion. What is still acceptable, and what is really wrong?

The story of the parts

The Mass in B minorr was never performed during Bach’s lifetime (the incomplete state of the Credo once again confirms this), and consequently there are no original parts. This can present a problem, for many things, particularly relating to the performance, were only resolved by Bach in the performance parts. Although these exist for Parts I (“Kyrie” and “Gloria”) and III (“Sanctus”), each of these belong to other versions of the work, and basically have nothing to do with the Mass in B minor. With the “Sanctus” the case is quite straightforward: the surviving parts are based on another, earlier score, and therefore relate only very indirectly to the Mass. And the parts of the “Sanctus” do not contain anything apart from slurs which is substantially missing in the score. Here, is was possible to put the parts to one side; only Bach’s articulation scheme from the early version of 1724 is detailed in a footnote.

With Part I everything is more complicated. Bach had written this so-called “Missa” in 1733 for the newly-elected Elector Frederick Augustus II. However, the dedication copy for the Elector only contains the parts; Bach kept the score and integrated it in 1748/49 into the score of the Mass in B minor. The score and parts therefore directly relate to each other. The parts of 1733 were made outside Bach’s working circle in Leipzig. Thus the copyists involved were not Bach’s Leipzig copyists, but a few family members and, above all, Bach himself. Now Bach was able to copy out Bach really badly without changing anything, and so the parts are not only heavily marked, but they also differ in numerous details (including notes) from the autograph score. But not enough: when Bach made the 1733 score into Part I of the Mass in B minor towards the end of his life, he again made alterations, and quite different ones, and in other places than in 1733. Actually it’s clear. The two sources are so far distant from each other that they cannot simply be amalgamated together: if that were the case, the result would be a work which never existed in that form historically. Unfortunately Bach’s score of Part I – as so often – is fairly incomplete. What’s missing is not only most of the practical performing instructions, but also details of instrumental scoring in the “Kyrie II”, the precise part-writing for the flutes in most of the tutti movements and also the use of the bassoon beyond the “Quoniam” is not stated in the score. In the “Dresden parts” of 1733, however, Bach had made decisions about all of these unresolved questions; the decisions which had to be made for the performance. Ignoring the parts entirely would not be a suitable solution either.

For my new edition of the Mass in B minor, the music text was initially edited strictly according to the autograph score as the main source, then the additional part-writing and markings of the “Dresden parts” were added in grey. And thus a performable version with all the necessary information has been created, but the two layers remain visibly separate (and it is clear how much is, in fact, missing in the autograph score!). As earlier in the “Credo”, transparency has been an overriding concern here – and also to expose “simple” solutions as being too simplistic.

Of course, even this transparent mixture only functions with limitations, for everywhere where the two versions have developed separately, a combination is barely possible.

The decision made by Ulrich Leisinger, the first editor to publish a Mass in B minor based on the NBArev, to follow only the “Dresden parts” in Part I, is certainly also due to the transparency of the NBArev: there we can see how considerably things have to be mixed up! Leisinger’s restricting himself to the parts has the advantage that he presents Part I as a “complete whole”, and can follow the parts without any compromise, including the often more elegant solutions which Bach found in writing out the parts. This is achieved, however, by separating Part I from the autograph score and its revision. In the process it’s precisely these revisions which incorporate Part I into Bach’s late works – and thereby also into the Mass in B minor – and which reveal the outlook of the older Bach, a composer who matured by studying the Palestrina style.

Every present-day solution is necessarily a compromise, and none can do full justice to the challenge of the Mass in B minor. Each is an attempt and should be acknowledged as such – but which nevertheless represents a positive attempt to rise above some older editions.

Uwe Wolf

(aus [t]akte 2/2015)